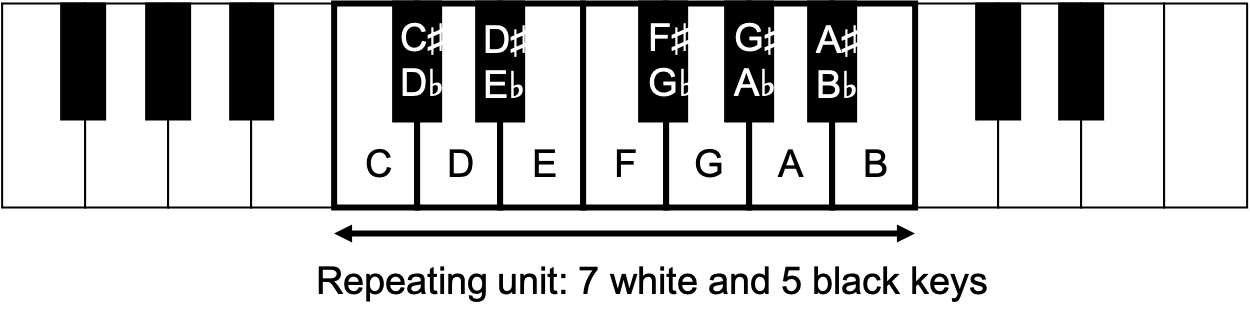

A standard piano has 88 keys: 52 white ones and 36 black ones. On the left hand side are keys that produce deeper tones with lower sound frequencies, on the right are the keys that produce higher tones. In principle there could be more keys on either end, but at some point the frequencies stop sounding musical in our ears, and more keys might become impractical for the performer. Older pianos may have 85 keys and there exist cheaper keyboards with even fewer keys. What all pianos have in common however is the following repeating pattern of twelve keys, including seven white and five black keys:

If you know a little bit about music, you will also be able to label each key with its corresponding note, as I've done in the image. But have you ever wondered why the keyboard looks like this? Why are there twelve, and why is there this pattern on the piano? Why do most musical instruments produce the same notes? Sound can be of any pitch, so it seems strange that in the context of music we collectively decided to limit ourselves to these specific frequencies.

You might have heard the answers to these questions are purely cultural matters: we are just accustomed to these sounds as music. But what if I told you that there might be a deeper mathematical explanation for why there are twelve notes, an explanation that relates to prime factorization of numbers and weird mathematical constructs known as continued fractions?

The fundamentals: sound and frequencies

Let's first review the basic physics of sound so that we can all start on the same page. Sound is produced by the vibration of air molecules. A loudspeaker works by vibrating a membrane at high speed, which causes the air near the membrane to compress and contract periodically. The air molecules bounce against each other which results in the propagation of the pressure wave. Note though that the air molecules stay in the same place and just oscillate around a neutral position. These concepts are nicely illustrated in animations on the website of Dan Russel from the University of Pennsylvania, as you can see in the one below:

You can see that if the input is some signal that is repeating or periodic, as would be the case with a loudspeaker or a vibrating string, then the end result is a periodic pressure wave. Because air particles that vibrate in the same direction as the direction in which the wave propagates, sound is a longitudinal wave.

Because we don't want to draw individual air molecules each time to represent the wave, we consider more abstract characteristics of the wave to represent it. For the purposes of understanding sound and music, all we really care about is how fast high pressure regions follow one another (the frequency) and how high the pressure gets (the amplitude). Our eardrum oscillates in sync with incoming sound waves. If the pressure peaks follow one another very quickly, the eardrum will also oscillate quickly (at high frequency), and our brain will interpret this as a high pitched sound. The reverse is true if the pressure peaks are widely spaced and the eardrum oscillates slowly. Higher amplitudes are interpreted as louder sounds.

For the purposes of this post, we are mostly concerned with frequencies of sound. These determine pitch, which lies at the heart of the different notes. Typically frequency is expressed in Hertz or Hz, which means how many cycles occur per second. If we hear a 5 Hz sound wave, this means that on average five pressure peaks reach the ear every second. The piano notes (and all other musical instruments) are calibrated such that the A above the central C has a fundamental frequency of 440 Hz. This specific value is quite arbitrary, and for a while there was disagreement over what the "reference frequency" should be. What is not random is how the frequencies of all the other notes relate to the reference frequency; it is their ratio that determines whether they sound nice together.

Of course pressing a piano key or strumming a guitar chord does not produce a wave of a single frequency, otherwise all instruments would sound the same. There are other frequencies mixed in with the dominant fundamental frequency which differentiates the sound of different instruments. For the sake of simplicity however, we will just talk about the main (fundamental) frequency of musical notes.

Harmony: sounds that work well together

It was Pythagoras that initiated the mathematical study of musical harmony. He discovered that strings that share simple integer length ratios produce sounds that tend to sound harmonious. For example, two strings with length ratio 2:1 produce notes that sound identical, except one of them is "higher" and the other "lower". Similarly, two strings with length ratio 3:2 produced a nice sound.

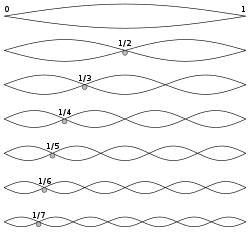

Essentially what Pythagoras discovered were overtones. When a string vibrates, it tends to vibrate in a mode that is some linear combination of the standing waves that can exist on the string, as illustrated in the image below. These are all the waveforms where the wavelength is \(\frac{2l}{n}\) with \(l\) the length of the string and \(n\) the positive integers, such that the wave amplitude is always 0 at both ends of the string. The reason this happens follows from the differential equation that governs waves on strings which is an interesting topic on its own with some interesting connections to quantum mechanics, but we will not explore it further here.

What is important is that each of these waveforms corresponds to preferred frequencies at which the string vibrates. The dominant frequency tends to be the one corresponding to \(n=1\), also called the fundamental frequency. The overtones where \(n>1\) also exist on the string and will always sound good with the fundamental frequency, i.e. a single string will be harmonious with itself.

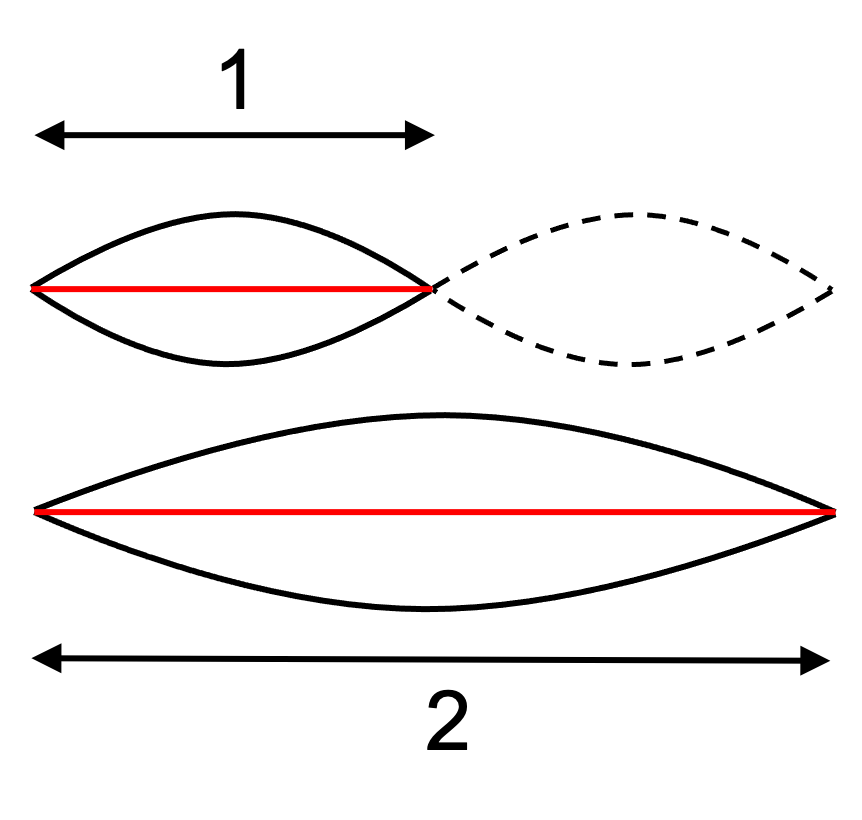

We can take this concept now and apply it to two strings. It's easy to see that a string twice as long as another string will have half the fundamental frequency of the other string (provided the two strings are made from the same material and the tension in the strings are the same). This means that the fundamental frequency of the shorter string is equivalent to the first overtone of the longer string.

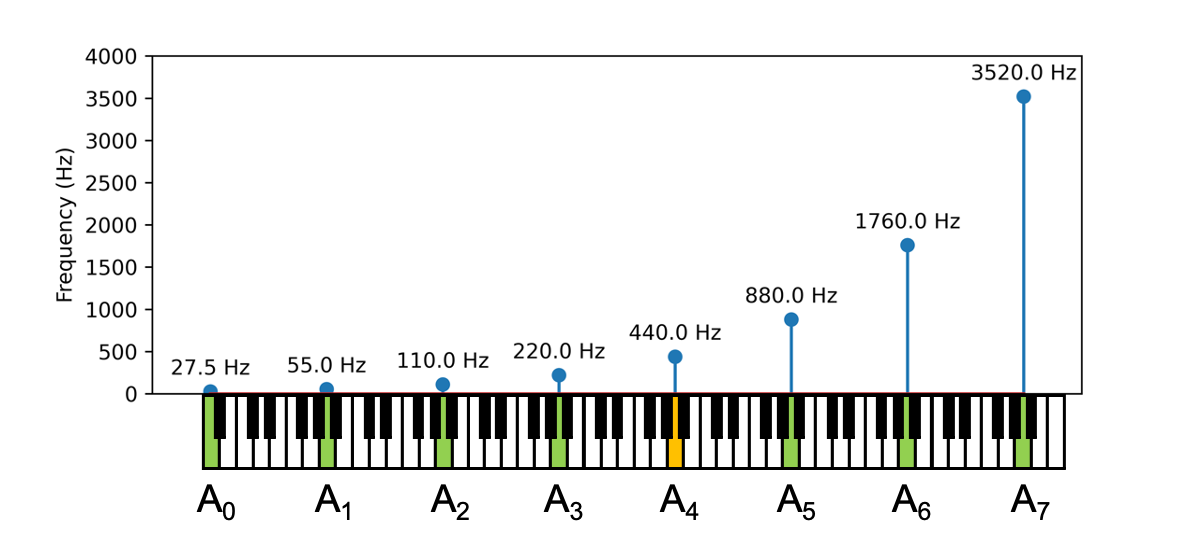

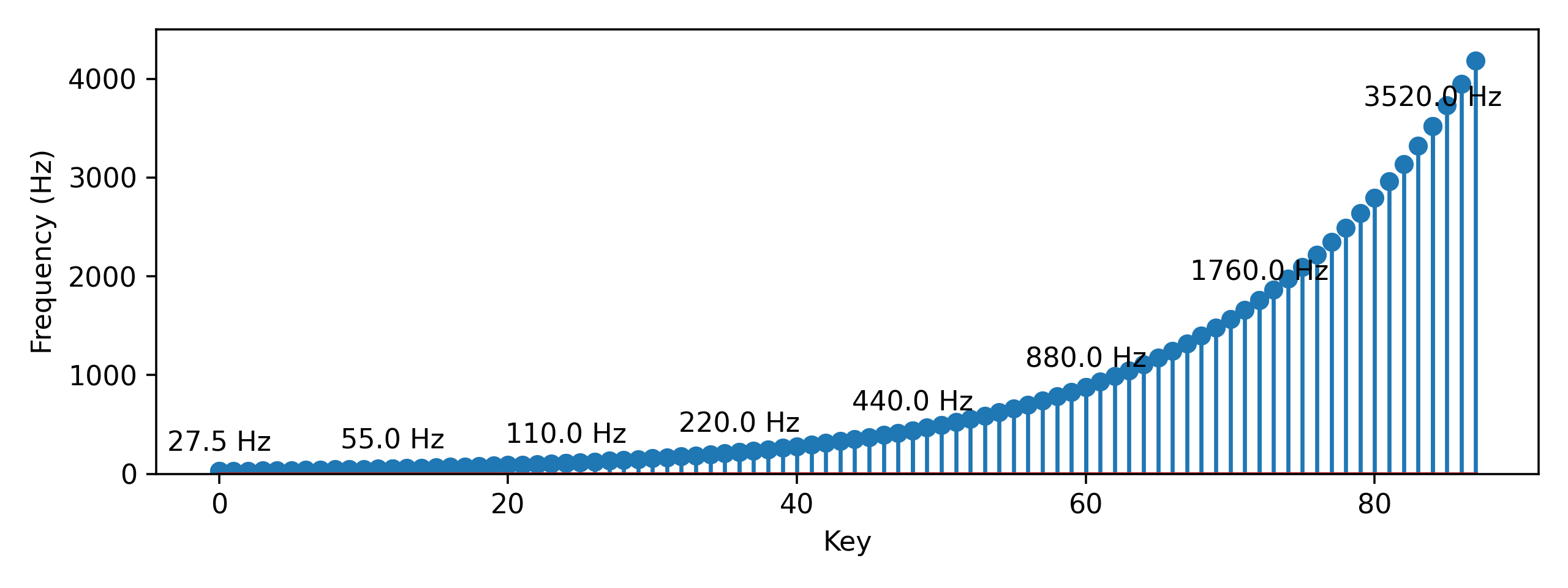

So the two strings produce harmonious sounds, and our brain interprets this as "sounding nice". In fact our brain interprets these frequencies as the same note, but one with a higher and another with a lower pitch. This is the principle behind the octave, or why the same notes repeat. With this information, you should already be able to work out that the frequency of consecutive A's on the piano differ by a factor of 2. So while the piano keyboard looks a bit like a linear axis, the frequencies of the notes actually follow a geometric series. With this information we can work out what the frequencies of all the A's on the piano keyboard should be, provided we use the 440 Hz standard.

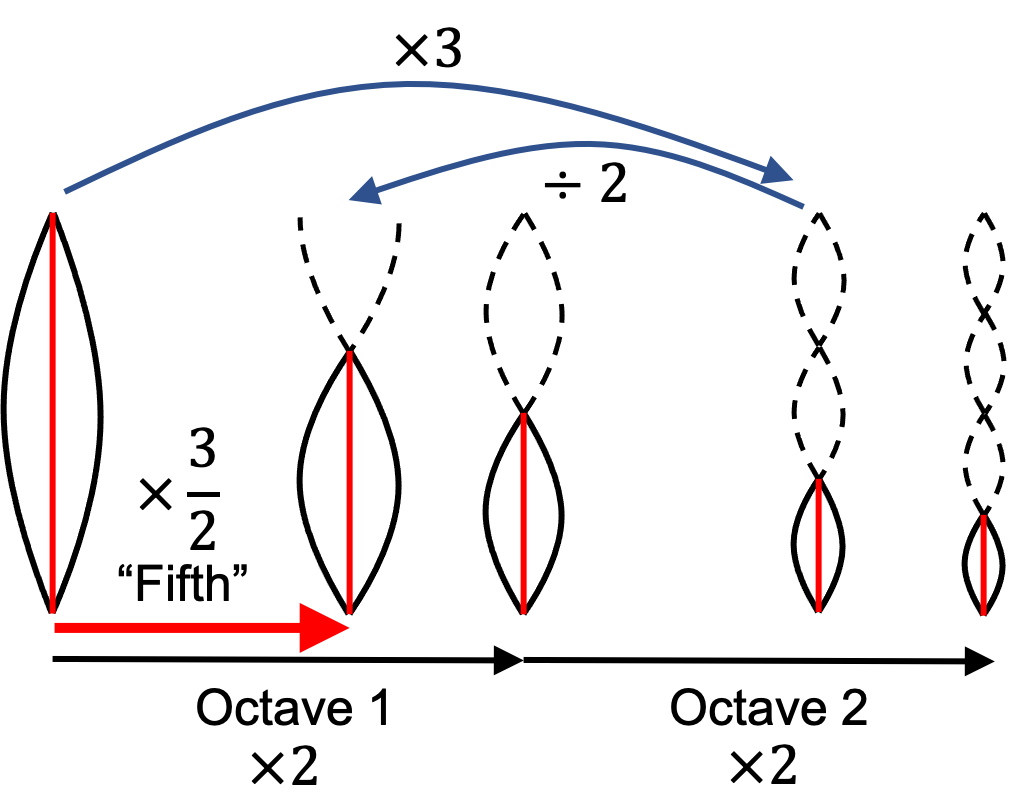

We following a similar argument for the Pythagorean ratio 3:2. A string of length 1 will have a fundamental frequency equal to the second overtone of a string of length 3. This also sounds nice and harmonious but does not sound like the same note. The frequency of the string of length 1 should be three times the frequency of the string of length 3. That means that the frequency must fall somewhere between the first and second octave (frequencies of 2 times and 4 times the longest string respectively). So now we've created a new type of note that sounds different to our brain! Now we can apply the same octave trick to this note as with the original note and create a corresponding note that sits somewhere in the first octave. Together with the base note this note forms the so called "fifth" interval, which is somewhat confusing nomenclature given that the frequency ratio is 3:2.

It turns out that, even though the fifth is not strictly an overtone of the fundamental frequency, they still sound nice together. To find the fifth on a piano, from any note count up seven keys from that note. For example, from C that would be G, from F that would be C, from D# that would be A#.

Just tuning: constructing all the notes with integer ratios

So how do we get to the additional notes in between? Your first instinct might be to just continue with the same idea of finding higher overtones. However, the third overtone (factor of 4) will just produce a second octave. From this you might already guess that only prime number multiplication factors will produce unique notes. The fourth overtone (factor of 5) will lie just beyond the second octave. We can create an equivalent note in the first octave by dividing by 4. The ratio 5:4 is called the "third" interval, and is found on the piano by counting up 4 keys. For example, from the C that would be the E.

Usually we don't go beyond the fourth overtone. Instead we combine the factors 2, 3 and 5 to create new notes with intermediate whole number fractions on the interval (1, 2). Basically, the frequency of any note can be expressed as \(f_0 2^x 3^y 5^z\) with \(f_0\) the reference fundamental frequency and \(x\), \(y\) and \(z\) all integers (negative exponents are also valid; remember that just puts the number in the denominator). Creating notes from whole number fractions of some fundamental tone is called just tuning.

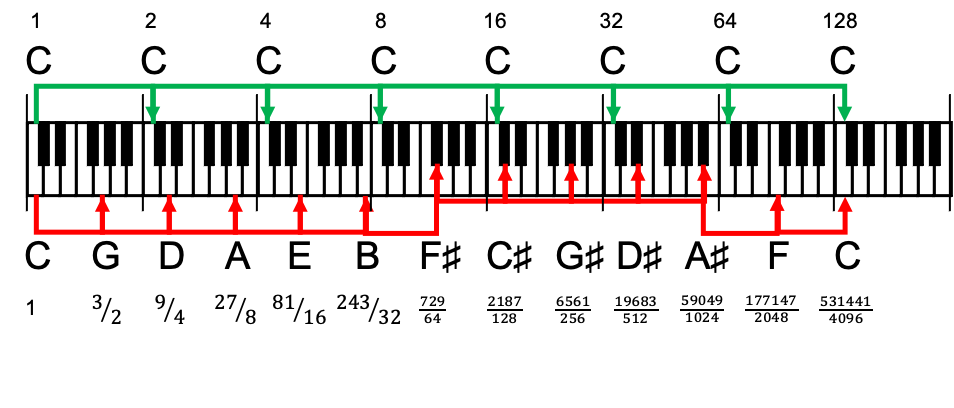

It turns out that we don't strictly need the 5: we can create sufficiently complex factors with just 2 and 3, i.e. \(f = f_0 2^x 3^y\). This is the Pythagorean tuning, a subset of just tuning. For the sake of keeping our argument simple, let's try to construct all the existing notes using only the factors 2 and 3. The factor \(2^x\) only rescales notes to different octaves, so only the \(3^y\) factor can bring us to new notes. Factors of 3 makes us skip at least an octave, so it is most convenient to illustrate the transition through all the notes with the factor \(\frac{3}{2}\) corresponding to a fifth. Without questioning the layout of the piano keyboard for now, let's find the sequence of consecutive fifths and octaves by incrementing by 7 and 12 keys respectively. We start from a low C:

The sequence of fifths is: C, G, D, A, E, B, F#, C#, G#, D#, A#, F and back to C. You can verify that this sequence really contains each of the 12 notes: the fifths pass through all the notes and then cycle back to the starting note. But notice that something doesn't add up: following the fifths, the frequency of the highest C should be related to the bottom C by a factor \((\frac{3}{2})^{12}=\frac{531441}{4096} \approx 129.75\), but following the octaves we find it should be 128. Where does this difference come from and which one is the correct frequency? Is there a way in which we can make the frequencies of octaves and fifths coincide?

Who says that 12 fifths should bring us back to C? Maybe 12 notes are insufficient, maybe we just need more subdivisions. Perhaps if we go far enough can we make the sequence of fifths line back up with the octaves. This problem, we can reformulate as finding integers \(x\) and \(y\) such that

or

An answer to this question would tell us that we need \(x\) notes to come back to the same note. But it is rather intuitive that there can never be an integer solution to this equation due to the fact that 3 and 2 are prime numbers. The left hand side can be any length string of 3's and the right hand side can be any length string of 2's: none will ever cancel on either side. The number on the left hand side will always be odd, the right hand side even. A more thorough proof can be found in the fundamental theorem of arithmetic which states that each number has a unique factorization into prime numbers or is prime itself.

The implication is that we can create an infinite number of different notes with fifths; they will never overlap with the octaves. This is problematic, because the intervals (ratios) between notes start to diverge: the interval from F to C on an upper octave will not sound the same as the same interval in a lower octave. There is also no way to decide what is a "real" note: do we construct them based on the fifths or based on the octave? The compromise that was agreed on for just tuning were the following frequency ratios, using C as the reference frequency:

| Note | Frequency ratio |

|---|---|

| C | 1:1 |

| D | 9:8 |

| E | 5:4 |

| F | 4:3 |

| G | 3:2 |

| A | 5:3 |

| B | 15:8 |

| C | 2:1 |

The octave is kept at the proper 2:1 interval. Notice that the factor 5 is used to construct these ratios, since this limits the denominators of the fraction; if we use pure Pythagorean tuning we need much less convenient fractions. The downside of just tuning is that music can really only be played in the key for which it is tuned. The intervals are not evenly spread out, which means that the same songs transposed to a different key will not sound good, and some intervals of notes should be avoided.

To solve this issue, most modern instruments use equal tempered scale. In this scaling, the factor between successive notes is constant; only the reference frequency and the octaves of the reference note are maintained. To divide the octave into 12 equal intervals, the ratio \(x\) between consecutive notes must adhere to the relation

In this way the frequency of all notes can be calculated as an element of the geometric sequence with factor \(x\), and it still respects the exact octave intervals for all notes.

The drawback is that no other interval other than the octave are strictly rational, but we come very close. For the fifth for example, we have \(x^7=1.498\) which comes awfully close to 3:2. For the third, \(x^4=1.260\) which again is very close to 5:4. For most normal people, the equal tempered notes sound perfectly fine, but technically most intervals are not as "pure" as they could be.

The bottom line is that any way you divide up the frequency spectrum into notes, you must make compromises due to the fundamental theorem of arithmetic. Unless you introduce an infinite number of notes to represent every possible rational. Which finally brings us to the question: why did we decide on 12 notes?

Twelve is close enough

Let's return to the question without an answer: finding integers \(x\) and \(y\) that solve the following equation:

By taking \(\log_2\) of both sides, we can rearrange this equation into

This means that the number of octaves \(y\) and the number of fifths \(x\) will coincide on the same note when their ratio is \(\log_{2}3\). We have established that this is impossible to achieve when \(y\) and \(x\) are integers; \(\log_{2}3\) is irrational. But maybe we can find a rational number \(y/x\) that best approximates \(\log_2 3\). With the fifths, we will pass through all the possible unique notes, factors of 2 just map the notes to the different octaves. Therefore \(x\) is also equal to the number of unique notes.

How can we find a rational approximation for an irrational number? Enter continued fractions, a mathematical concept that was already studied by the ancient Babylonians. The idea is best illustrated by directly calculating the continued fraction representation of \(\log_{2}3 = 1.589625...\). First we separate off any integer term and a leftover term \(<1\), so in this case 1.

We take the reciprocal of the leftover term, which will again have an integer term that can be decomposed.

We repeat this same process of taking the reciprocal of the fractional part and splitting the integer component. For an irrational number this process can be repeated indefinitely. If the continued fraction expansion would have a stop somewhere for an irrational number, then one could work backwards, combine all the terms and reduce the fraction to its canonical representation, which would contradict that the number is irrational. For the first few iterations, the continued fraction of the number we are interested in will take the form:

More succinctly we can represent the continued fraction with just a list of coefficients or terms, in this case \([1;1,1,2,2,3,1,5,...]\). The interesting thing about continued fractions is that we can truncate them after each coefficient, to reach better and better rational approximations of the irrational value. The value of the fraction after truncation are called the convergents. In our case, the first few convergents of the fraction are shown in the table below. The relative error from the real value of \(\log_2 3\) is also shown.

| Expansion | Convergent | Error (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [1;] | 1 | -36.9 |

| 2 | [1;1] | 2 | 26.2 |

| 3 | [1;1,1] | 3/2 | -5.36 |

| 4 | [1;1,1,2] | 8/5 | 0.949 |

| 5 | [1;1,1,2,2] | 19/12 | -0.103 |

| 6 | [1;1,1,2,2,3] | 65/41 | 0.0254 |

| 7 | [1;1,1,2,2,3,1] | 84/53 | -0.00359 |

| 8 | [1;1,1,2,2,3,1,5] | 485/306 | 0.000304 |

Naturally as we add more terms, we approach the irrational value more closely. The convergence is also quite rapid. In this expansion the convergents represent estimates of the ratio \(\frac{y}{x}\) where \(x\) is the number of unique notes until we return to an octave, and \(y-x\) is the number of octaves until the fifths have made a full revolution. You will immediately see that one of the convergents corresponds to the situation we illustrated on the piano keyboard: 12 notes and \(19-12=7\) octaves until we've made a full revolution with fifths through all the different notes.

A property of continued fraction convergents is that they are guaranteed to be "best rational approximates" of irrational values. This means that the convergent \(\frac{p_i}{q_i}\) with integers \(p_i\) and \(q_i\) will better approach the irrational \(\alpha\) than any other rational number with a denominator smaller than \(q_i\) i.e.

For example, the fourth convergent \(8/5\) will be a better approximation of \(log_2 3\) than any fraction with numerators 1, 2, 3, or 4. Indeed numerators 1 and 2 are already in the table and are worse approximations. For numerator 3, the best numerator we can find is 5, and \(\frac{5}{3}\) differs about 5.16% from the true value. For numerator 4, the best numerator is 6, so we end up back at the fraction \(\frac{3}{2}\). So \(\frac{8}{5}\) does better than any of the other options. This will be true for all convergents of the continued fraction, so \(\frac{19}{12}\) will be a better approximation than any fraction that can be constructed with a numerator between 1 and 11. For those interested in the proof it can be found in the book "Introduction to Diophantine Approximations" by S. Lang, Chapter 1, Theorem 6.

So with 12 notes we end up quite closely back to an octave with fifths. But this should also be the case for 5, and 41 and 53 notes. It makes sense that we would limit ourselves to a manageable number of notes; at some point the tones are too similar to distinguish them. But is matching fifths and octaves really that important?

Twelve provides good note spacing

There is an additional reason to use 12 notes. Suppose we create new notes with fifths, but we always remap the new note to the first octave using factors of 2. This means all our notes are on the frequency interval fraction (1, 2). To make things easier to visualize, we now shift from a linear scale to a logarithmic scale. If we take \(\log_2\) of the frequency ratios, then the reference frequency on the log scale is 0, and the first octave is at 1. Our first fifth will be positioned at \(\log_2 \frac{3}{2} = \log_2 3 - 1\). On the linear scale, to find the next fifth we multiply by \(\frac{3}{2}\), but on the log scale we add \(\log_2 3 -1\). Since we want to be constrained to the first octave, we really have to work in a modulo 1 system. So the \(log_2\) of our fifth frequency will be

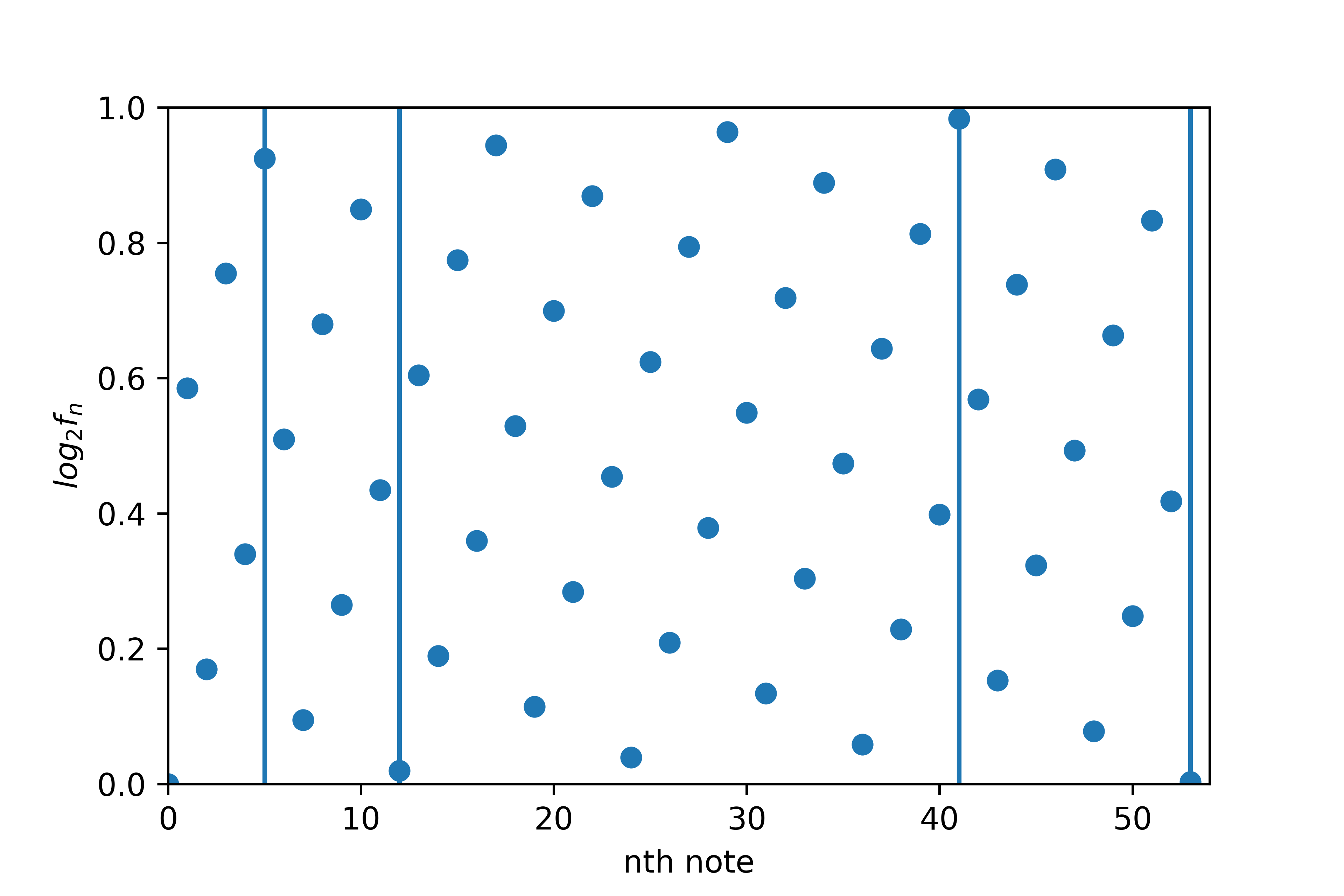

The \(-1\) can be removed due to properties of modular arithmetic. To go back to our linear scale of frequency ratios we simply raise 2 to the power of each side. Plotting these out for the first 53 \(n\) yields this interesting lattice:

The denominators from the first 4 reasonable continued fraction truncations are also shown as vertical lines: 5, 12, 41 and 53. The values coincide with points that are close to either 0 or 1, which is what we expect since the continued fraction truncations should give us the points where the fifths best approach the octave.

We can also visualize the modularity using complex numbers, by wrapping the points on the unit circle. A single rotation around the unit circle on the complex plane is given by \(e^{2\pi i}\). The full octave on the log scale will represent a full rotation. Extending the same logic, the complex representation of the \(n\)th fifth \(c_n\) is calculated with

The number of fifths also tells us the number of unique notes we create. We have an implicit desire that our notes span the tone range as fairly as possible, i.e. that notes are more or less equidistant from eachother. Perfectly equidistant notes can be achieved only using the equal tempered scale as discussed earlier. On the linear scale, consecutive notes in equal temperment are related by the factor \(\sqrt[n]{2}\), on the log scale consecutive notes simply differ by \(\frac{1}{n}\). On the unit circle in the complex plane, these notes can be represented by

This represents points on the circle circumference that are equally spaced. Both sequences are shown for increasing number of notes below. The blue squares represent the equal tempered notes, the orange points represent the just tempered points. All perfect fifths are connected with a line, and the last fifth is connected again to the reference note. You see that most of the continued fraction truncations (besides 41) result in nearly rotationally symmetric star patterns, which gives a pretty decent match with the equal tempered scale. The animation pauses for a bit on the values that correspond to the continued fraction truncations.

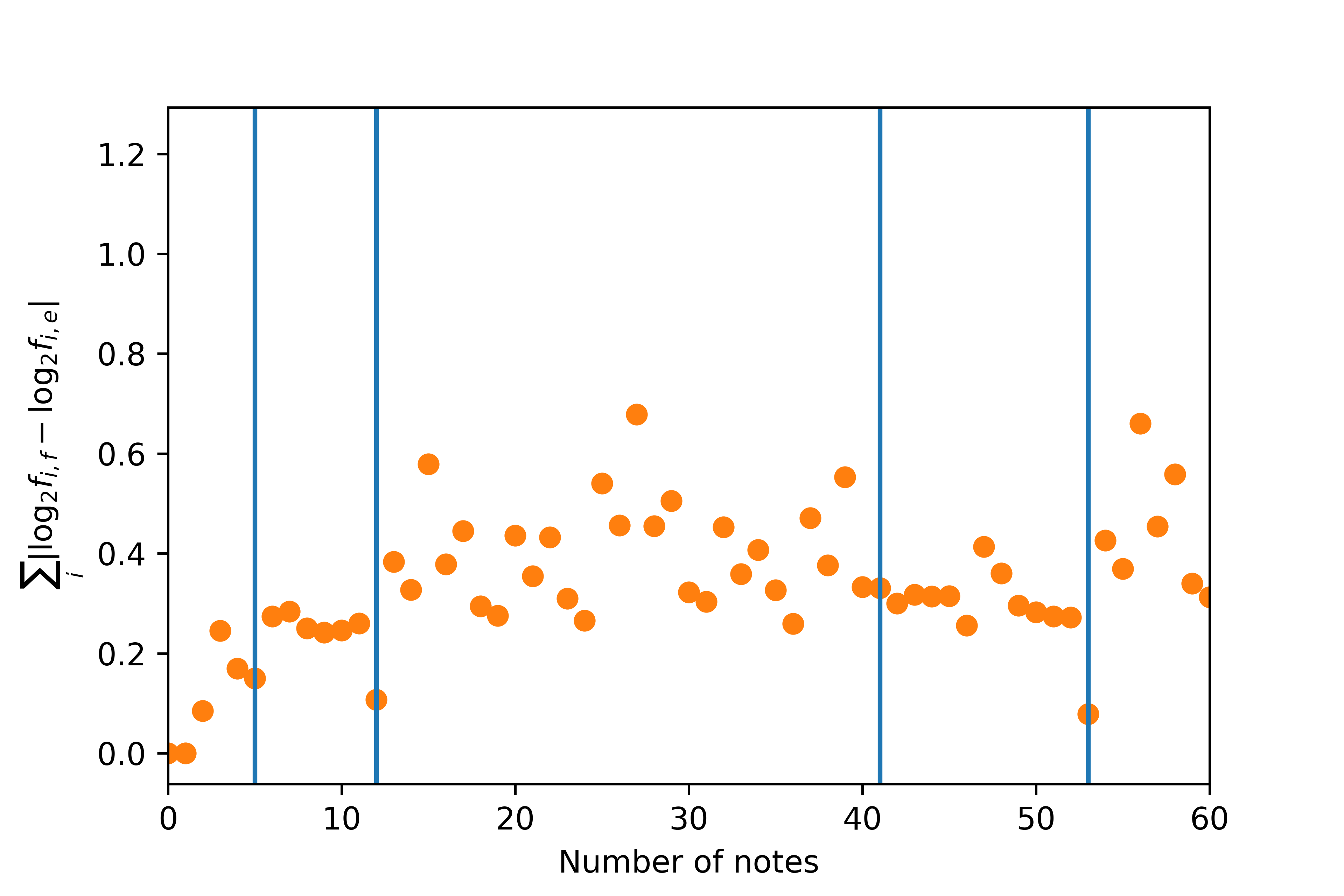

We can formalize this observation by calculating the deviation between all the closest \(\log_2 f_{i, e}\) calculated from equal temperment and \(\log_2 f_{i, f}\) calculated from fifths, then summing all these values. The result is the plot below. Again the first relevant continued fraction truncations are shown as blue lines.

As you can see, 12 and 53 break the general trend, and have a substantially lower average deviation to the equal tempered notes, indicating a rather fair note distribution. 53 notes is just not practical; consecutive notes are too close together to properly hear the difference, and the likelihood of playing dissonant combinations of notes increases, so we choose 12 notes.

Five notes is also not too bad and it is also a denominator in the continued fraction convergents sequence. The presence of 5 in the sequence may explain the layout of the black keys on the piano keyboard: if we start from the reference F#, then we can pass through all the black keys using fifths before we end up on a white key. The frequencies of the black keys could be stretched a bit so that they form the entire note system with only five keys, i.e. we end up back at F# after A#. Indeed there exist historical music systems that only had five notes, for example in ancient Greece. The black keys on the piano approximate the pentatonic scale; you can often play beautiful music using only these keys. The white keys are then added to get to 12 notes. In case we want 53 notes, we would need to add an additional "layer" between the white keys.

Not all denominators of continued fraction convergents lead to fair sampling. While 41 fifths brings us back very close to the octave, 41 notes don't sample the octave range all that well.

Summary

In this post we attempted to answer the question why we have twelve musical notes. To create good sounding notes we want them to share simple frequency ratios. However, it's not possible to simultaneously have simple frequency ratios between notes and equally spaced notes. The convergents of a continued fraction expansion can tell us which number of notes gives us the best balance between these conflicting requirements. As it turns out, 12 meets those criteria with a manageable number of notes.

Appendix

If you want to calculate your own continued fraction expansion it can get a bit tedious with pen and paper. Below are two python functions, one to calculate the continued fraction expansion of a value, and a second to evaluate convergents of a continued fraction (with the terms provided as a list).

from fractions import Fraction

def continued_fraction(value, stop=10):

terms = []

while len(terms) != stop and value != 0:

div, rest = divmod(value, 1)

value = 1/rest

terms.append(div)

return terms

def evaluate_continued_fraction_expansion(terms):

copy = terms.copy() # avoid changing the original list

value = 0

while len(copy) > 0:

element = int(copy.pop())

if value == 0:

value = Fraction(element)

else:

value = 1/value + element

return value